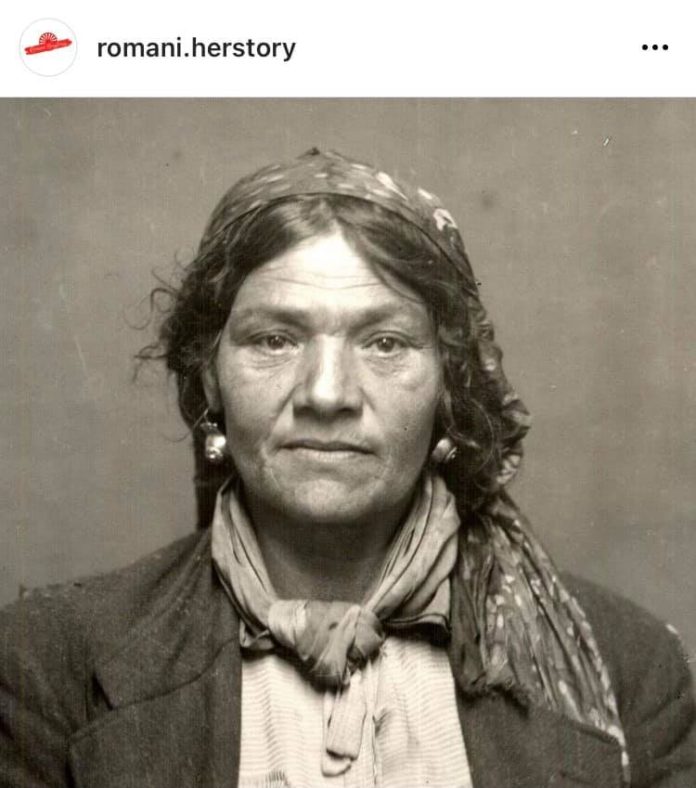

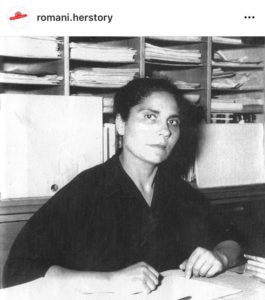

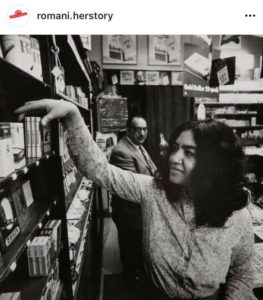

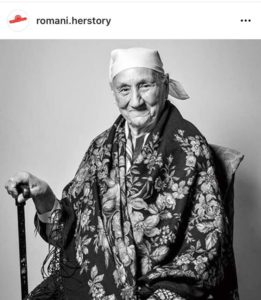

It is well known that in many countries across Europe, the Roma community continues to face social exclusion, lack of access to quality health services or education, as well as challenges in finding employment and adequate accommodation. Romani women stand out in particular, who in their struggle to be seen and heard are sometimes excluded even from feminist circles. I spoke about this and related topics with Émilie Herbert-Pontonnier, a researcher and media expert of French, Belgian and Roma-Manouche origins. In addition to a degree in filmmaking from Kingston University in London (UK), Herbert-Pontonnier also earned a PhD in Media, Culture and Communication from the University of Liège (Belgium) in 2019. Although with little experience on social media, on International Women’s Day 2020, she opens an Instagram account and symbolically calls it Romani Herstory, which becomes the site of short biographies that tell the life stories of Romani women, unsung heroines or seekers who refuse to conform to stereotypes.

Thereby, it is possible to read the story of Panna Cinki, an 18th century Romani-Hungarian violin virtuoso who challenged the contemporary societal conventions on gender, or Ellen Chapman, a 19th century wild beast tamer also known as “Madame Pauline De Verre, the Lion Lady”, but also because she was a quiet person who treated her animals with a certain tenderness, instead of using a whip and a stick. There are also Romani women with whom we share the present, such as Ana Maria Crina, a young girl from Romania who, driven by the desire to help those around her, perfected her craft of white magic for many years; Erika Varga, an award-winning fashion designer from Hungary; sisters, actresses and musicians Simonida and Sandra Selimović, Serbian natives; journalists Hedina Tahirović-Sijerčić, Gilda- Nancy Horvath and Silvia Agüero Fernández; politicians, scientists, lawyers, athletes, writers… In countless ways, Romani women contribute to the advancement of their respective communities, and my interviewee points out that there are positive examples, but not enough visibility. The Romani Herstory digital archive thus provides a narrative opposite to that which silences and erases the enormous societal contributions of Romani women.

How did you come up with the idea of starting a digital library and what prompted you to do it?

At first, I did not envision that the project would lead to a digital library as such. Romani Herstory started as an Instagram page in March 2020. My goal was to research, write and publish the stories of 100 Romani women who had inspired me and whom I thought would inspire others as well. At the time, I was working on a research project about Romani gender activism and identity construction from a female perspective. I had just discovered women like the Pankova sisters, Philomena Franz and Aranka Hegyi, and I remember thinking: How is it possible that I had never heard of these amazing women before today?!

Most of the researchers who have approached our communities since the 19th century have focused on the male experience of Romani life and culture, resulting in a large disinterest in women’s issues. Even today, the tendency to frame us as never-ending victims seems to be a persistent trend in most academic and media discourses. When I started this project, I wanted to capture the idea that our experiences are not solely defined by invisibilities, discrimination, and trauma. That our collective herstory can also be one of successes, achievements, resistance, solidarity… After a year, it was clear that even a hundred portraits were not enough to show the diversity and the richness of Romnja’s contributions to society, so I kept writing! But I wanted to push the project a little further and create a proper website that could act as a digital library, but also offer other resources such as guest contributions and lists of books, articles and media material. It is still a work in progress but it is growing.

Your research interests focus on issues of gender, cultural diversity and cultural production. What new findings did you come across when collecting data and sharing content about Romani women?

One of my favorite research projects has been the essay I wrote about Romani women filmmakers, with the support of the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture. It really blended all my research interests into one work! I think that most people are used to see Romani women as the objects of representation but rarely as active cultural producers. Unfortunately, it remains extremely hard for Romani women to enter the cultural industries: often excluded from traditional means of production and distribution, most of them have worked within the independent sector which has, at times, exacerbated their invisibilities. But it doesn’t mean that Romani women haven’t left an important cultural legacy behind them. In this essay, I identify 23 women directors of Romani descent and offer a filmography of more than 120 short and long-feature films, directed between 1981 and 2020. It’s a shame that these films are not better-known and more easily accessible.

We know that the lack of visibility and participation is reinforcing the social exclusion of Romani women and is associated with low levels of social wellbeing within Romani communities and Romani women can play an important role in breaking stereotypes and the situations of disadvantage. You yourself have stated that Romani women do not suffer from a lack of positive examples but from a lack of visibility.

It’s quite frustrating to be constantly confronted with the same stereotype – that Romani women are uninterested in education, that they do not contribute to society… Yes, access to formal education remains a site of struggle for many Romani girls and women. But, regardless of their academic credentials, Romani women are an essential part of European societies – as citizens, artists, scientists, writers, activists, they have contributed to improving their environment in a myriad of ways. We just don’t hear often about it. The digital archive aims to provide a counter-narrative and to undo this silencing and erasure.

What are the reactions of Romani women, but also the wider community, to the digital library you started?

The reactions have been positive, from the very start! I love receiving suggestions or messages of encouragement from other Romnja, it really is what keeps me going when I’m tired or when I lose motivation. It brings meaning to what I do when someone takes the time to share how happy or excited they are to read these stories.

Some Romani women have been curious about who “hides” behind Romani Herstory. I’ve always wanted the project to put the spotlight on Romani women and their achievements – my job is simply to write about them. My goal is not to be a social media influencer, not that there’s anything wrong with that, but what is important to me is to create visibility for all of us, and I do not wish to personify that struggle. Yet, I understand why it is important for some people to know who is behind such a project. So I’m trying to find a balance now and share as many personal details as I feel comfortable with so that other Romani women know that Romani Herstory is a safe space, made for them, by one of them.

I have to say that although some Romani men have been very supportive, overall, they haven’t interacted a lot with the project! Perhaps they think that they wouldn’t be welcome? In fact, I would love to involve more men in the project, for example through the blog section, where I publish external contributions.

In Romani Herstory digital library it is possible to read short biographies of Romani women as well as various resources about Romani gender activism. The media and art has largely helped to shape an image of Romani femininity that either fetishizes Romani women or discredits them. Has representation of Romani women in popular culture improved and how important is diversity of female narratives that help opening the question of the need to reconstruct the concept of Romani and female identity?

I don’t think that the representation of Romani women has improved drastically over the years. We are still confronted with stereotypical and essentializing depictions of our experiences on a daily basis – whether it is on screen or in the newspapers for example. But I’m excited to see what young artists, filmmakers and playwrights like Alina Șerban, Mihaela Drăgan, Lisa Smith, Vera Lacková or Laura Halilovic will produce in the upcoming years! Their work challenges mainstream representations of Romani women as exotic/erotic figures without agency or self-determination and, most importantly, contribute to diversify our narrative.

We should encourage young Romani girls to consider the media as a possible professional route – this is what another filmmaker, Katalin Bársony, is doing in Hungary through the Buvero camps, where young girls are trained in storytelling, journalism and documentary filmmaking. I strongly believe that representation is a matter of social justice. As long as we will continue to see our experiences portrayed under the prism of stereotypes and clichés, we will struggle to think of ourselves positively.

In one of your works you wrote that Esmeralda has taken over the Internet and is reclaiming her seat at the table. You are French woman of Romani descent and Victor Hugo and his The Hunchback of Notre Dame is well known and has been described as a key text in French literature. How your own childhood was marked regarding that and what memories do you carry from that period?

I think that I have a love-hate relationship with Esmeralda! I was 1 when the Disney adaptation was released in cinemas but I was mostly marked by the book which, as you mentioned, is a key reading in the French school curriculum. Hugo’s original description of Esmeralda is a little different from what we know of her American better-known counterpart. She is equally over-sexualized and presented in an exotifying way, but in the novel, Esmeralda’s exceptional beauty is only due to the fact that although she was raised as a Roma, she is not one, as she was abducted at birth. As a child, I found this extremely confusing and it exacerbated the feeling of shame and discomfort I had towards my Romani identity. The novel is unbelievably racist and I don’t hold Esmeralda as a role model. But she was one of the rare figures I could sort of identify with as a child, and I still find her generosity and compassion inspiring.

When I was a little girl, my family was moving a lot and it was really difficult for me to make new friends. In fact, I was consistently bullied in every school I went to. It made me shy, introverted and distrustful. I know that decades later, this is still a common experience for Romani and Sinti children, unfortunately. Neither of my parents had the opportunity to finish their education and they had both left school before the age of 16. I learned to read when I was 5 years old and would devour books, encouraged by my parents who wanted their children to go further in life than they had. Our earliest perceptions of the world can be shaped by the books we read so it’s essential that children see a true reflection of society in the literature available to them. I would love to see more positive representations of Romani history and culture in children literature, so that our little ones can find role models that look like them. Recently, Tayo Awosusi-Onutor, a German Sinti singer, filmmaker and activist, published a book in German entitled Jekh, Dui, Drin. Freundinnen in Berlin. It follows the adventure of three little Romani/Sinti girls and is a very endearing story – this kind of book would have been much more empowering for me to read at 10 than The Hunchback of Notre-Dame!

What social platforms do you use in sharing content and how do you comment on the benefits of social networks in self-representation of Romani women as well as increasing their visibility? Also, you are aware that many Roma may not have access to communication technologies or lack the digital literacy needed to use social media effectively.

I share most of the content on Instagram but I recently launched a Twitter account as well. Social media have enabled Romani women to create new patterns of activism and to connect beyond geographical borders. I personally learned a lot by connecting with Romani women from other communities and nationalities, and these virtual friendships have considerably enriched my work but also my personal life. By claiming these virtual spaces, we are affirming that our existence is valuable, in a world that has largely been denying it for centuries. Online hate speech remains a reality for most of us and can be extremely draining, but I’m convinced that social media can be really effective tools – to educate, raise awareness and create solidarity.

Yet, I know that many Roma across Europe do not have a computer or internet access at their hom or do not have a permanent home at all in the case of families who live in informal settlements for example. Pre-Covid 19, I used to be more active in the field and I know that it can be a much more complex and sometimes violent reality compared to “digital activism”. So I’m aware of the limitations of a project like Romani Herstory. Lately, I have been trying to secure funding to create printed multilingual educational booklets for a younger audience, so that Romani children and teenagers , and especially girls, who do not have an easy access to communication technologies can still learn about the inspiring Romani women that are present in the archive.

How is it possible to get involved in the work of a digital library and what can anyone do for the purpose of change?

Subscribe to the newsletter, share your favorite “herstories” on social media; donate through the platform, if you can, to help support Romani-led grassroots organizations working towards Romani women and girls’ education, follow @romani.herstory on Instagram too – it helps the project get noticed and grow bigger. Also, support these fantastic women: buy their books, their music, their artwork! I’d like to include more women entrepreneurs in the archive as well, as there are so many talented and hardworking Romnja who run their own business and deserve more visibility.

What are your plans for the future? Do you plan to expand your database with new sub-projects?

Romani Herstory is an ongoing, ever-growing archive so new content is regularly being added and I’m excited to see the database grow larger in the future – and, hopefully, be available in different languages, including Romani. I definitely want to continue to organize fundraising campaigns and use the platform not only as a space for celebration but also for education, awareness and community support.

But I’m also hoping to develop sub-projects such as the educational booklets I was mentioning above. I’m also dreaming of directing a short animated series based on all these inspiring women: animated films are typically rather expensive to produce but they are more accessible and can have a positive impact on a younger audience. I hope to find collaborators and partners to help me make this dream a reality.

The publication of this text was supported by the Electronic Media Agency as part of the program to encourage journalistic excellence