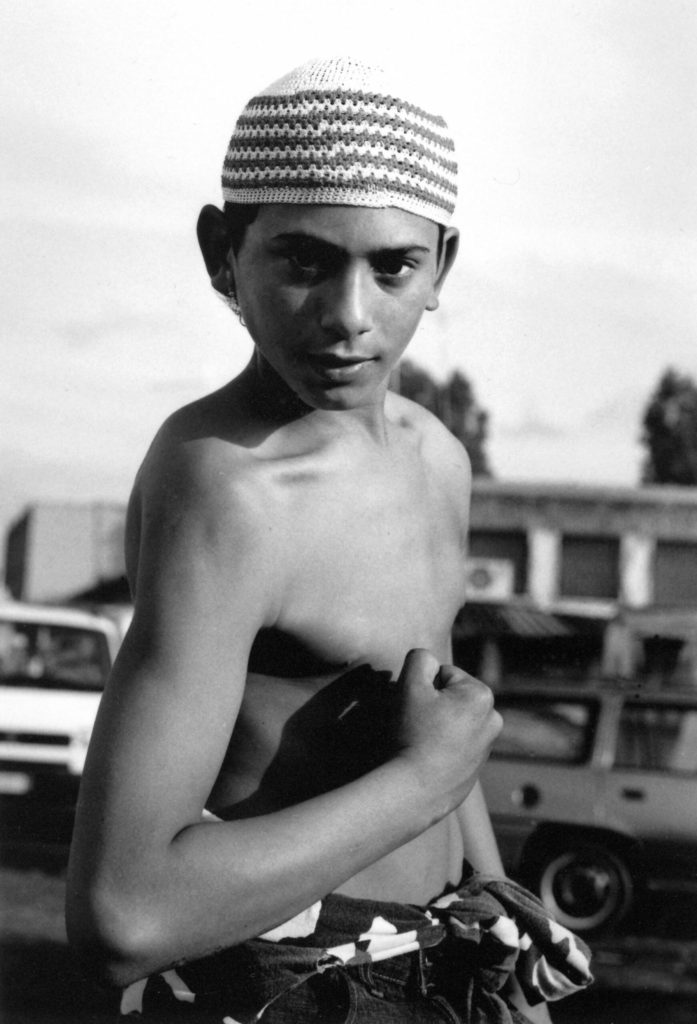

Nihad Nino Pušija is an artistic photographer born in Sarajevo. His work focuses on documentary and portrait photography, illustrating Romani identity on the streets of Berlin, where he has lived for the past 30 years, and in other parts of Europe. In 2001, Pušija attended Marina Abramović’s classes at the Art Academy in Braunschweig, and exhibited at the first two Roma pavilions at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2011, respectively. His monograph Down There Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, which covers his thirty years of work, was published in 2018. Pushija is preparing a new monograph with the symbolic title In Search for El Dorado, which embodies, as he states in the interview, the Roma community’s search for a golden middle and an ideal place to live.

You had your first exhibition in Sarajevo in 1988. What did that mean for you as an emerging photographer then?

I started working in the Sarajevo daily newspaper Oslobođenje in 1986. I was very young and studying journalism and political science at the time. I was also a member of a photo club – you know how it is. We photographers must also have a place to meet, exchange experiences, progress, and learn. There was no academy for applied and artistic photography in Yugoslavia. Education was only possible at film academies or as part of the graphic design at art academies. Then, a program where photography was partially taught only existed in Zagreb. After two years of taking photographs, Sarajevo became too small for me. Events, things, and faces started repeating themselves, but also the setting where everyone knew everyone started to annoy me. It was easy to travel then so I took my passport and went to London, where I spent almost four years.

However, before leaving, I did an exhibition in Medjugorje. That first independent exhibition dealt with the phenomenon of the apparitions of Saint Mary and religious symbols that were not popular during socialism. Back then I realized that photography is powerful because it shows people things and phenomena, regardless of whether they believe in them. It has its educational notes. On the one hand, showing religious themes in photos was not easy because I had to ask for permission from some institutions, and on the other hand I had to deal with church leadership. At the opening of the exhibition, various religious representatives were present. The Hodja invited me to come to the Islamic community to take photos: ‘Nihad, you are a Muslim, come to our place to take pictures’, and then the Orthodox priest said to me: ‘Well, well son, your grandmother is Orthodox, so come to us too’. I come from a mixed family, my mother is Catholic and my father is Muslim. At that time I was into alternative music and went to London because I didn’t want to record at the request of others. More importantly, I realized that photography offers me the possibility of entering a world where it can be representative. If you work on one theme for a long time, you enter that world. The only problem with some photographers is they never get out of the world they entered. I started focusing on people, and my photographs, mostly about the street, always had strong connections with people. The margin of society, that’s my topic.

Throughout history, the photographic representation of Roma has often reflected stereotypes. How do you see the role of photography today, especially through informing and raising awareness about a certain topic? Does photography still have the power to inspire action?

We, Roma, have always been neglected in this way. During socialism, it did somehow function but only because Roma had rights. For example, in Sarajevo, we had radio, magazines, and a TV show. In the early 1990s, when the Eastern Bloc opened up and the war began, all that disappeared. And that was a big problem. At that moment, I started working on a photo series about the Roma called Neglected Europeans. In Western European countries, a social system still existed to support those unemployed or without housing. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, and especially with the war at home, minorities were rejected, and the focus shifted to national identity. The Roma were the first to lose their jobs because they usually did simple jobs. Therefore, when you lose your job, the loss of your apartment, homelessness, and other things come as a consequence. The housing process is still critical in our Roma communities. A lot of Roma seem not to exist, they don’t have documents, are not registered, and don’t have the right to health insurance. That series of photos also marked the first Decade of Roma Inclusion, from 2005 to 2015. It was an intense moment of investing in Roma programs. Then the situation improved a little, but essentially people’s consciousness did not change or changed very little. You have now seen the results of the European Parliament elections. It’s not going well.

You were part of the 1st and 2nd Roma pavilions at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2011, respectively. Then you stated that as an artist, caught up in the transition process, you have the opportunity to create and explore Berlin. A metropolis where the two halves of the city are trying to live together again. This simultaneous merging and division of the Eastern and Western blocs is also the subject of your work.

Although I wanted to go to London, because of a friend I ended up in Berlin. In 1992, a few weeks after the fighting and bombing of Sarajevo, I left the city and then came to Berlin using some connections. I planned to stay there for a short time. At one point I noticed that the City had incredible potential and that this division, the Wall, is a powerful symbol. It reminded me of our reality, the ethnic division in our areas. Although here we have Germans on both sides of the Wall, they have different ‘mindsets’, which is normal considering the influence of capitalism and communism on opposite sides. It was a collision of worlds, when the Wall fell, work began on unification, which was an interesting process that continues, I would say, to this day. I have friends from the eastern part of Berlin who rarely go to the western part and vice versa. This is especially pronounced in the elderly, younger people do not remember it. That transition was interesting because of photography, and a large part of my work at the time was documentary photography, transitioning from one system to another. I published this in the first monograph, which includes works created in the period from 1988 in Sarajevo to 2018 in Berlin. I am currently working on another monograph, which deals with Roma and their representation through photography, and which is being developed as part of the program by the Senate of Berlin and the European Roma Institute for Art and Culture (ERIAC), which is one of the project’s leaders. The book is called Searching for Eldorado, that is, searching for the Golden Valley, the ideal place, paradise, and success. This is symbolic of the Roma community, as well as the phenomenon of travel and movement. Although we are no longer nomads, this is how we conduct ourselves. We are nomads because we are looking for a place where we, like all people, feel good. Where we can have our family, where children can go to school, and so on. When people say that we are used to traveling, that is nonsense, we don’t need it, no person in the world does not want to live in one place. No Roma would wish that, I’m sure.

In the second half of the 1990s, you led a group of young artists and students who had to abandon their studies because of the war in the former Yugoslavia. What topics did the “Zyklop photo factory” (Cyclops Photo Factory) project deal with?

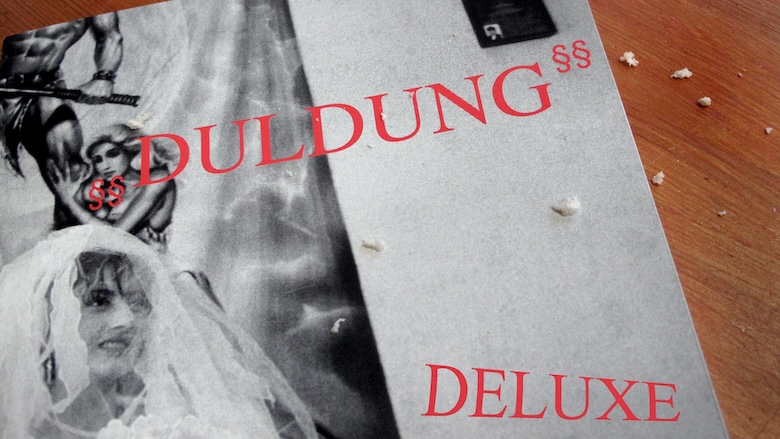

By coincidence, many young people found themselves in Berlin in the early 1990s. In addition to refugees, there were also young people, deserters, or those who did not want to participate in the war, among them a large number of intellectuals. Again, the Senate of Berlin stepped in with funds and we got a small space for socializing. At that time, I had already been abroad for four years. When you come to Berlin as a young person, insecure and in need of help, who gets exposed to alcohol and drugs in clubs and concerts, it is important to have a sense of belonging. In the photo club, we dealt with two issues, integration, because we had ten young people and then fifteen Germans joined us, which made one international group, and Duldung. It is a legal status in which the suspension of the current deportation of foreigners is in force. Duldung does not constitute a residence permit, because the holder must sooner or later return from where they came. These people did not even want to stay in Germany, they believed that the war would soon be over and that they would return home, so they had no possibility of employment or study. And that was frustrating.

Today the situation is different. When the Ukrainians came, they were automatically integrated into society, we didn’t have that before. In addition, it was worse for Roma, because they were even more segregated, and more vulnerable than other refugees, especially regarding accommodation facilities and homes. I dealt with this a lot, which resulted in a catalog and an exhibition within the framework of the New Society for Fine Art (NGBK) in Berlin, an association of contemporary artists of which I have been a member for thirty years. We did an exhibition called Duldung in 1997, a project of the Zyklop photo factory. Many people went back home or to other countries. I kept “fotofabrika” from the title of that photo group, which represents my personal project.

With the advancement of mobile phones, photography has never been more accessible and immediate. What do you consider the future of photography in the context of technological achievements?

Good question. What I can say is that if I were young now, under no circumstances would I take up photography again. At that time it was different and had some charm and maybe some deeper meaning. Everything is fast now, I haven’t been involved in press photography for almost two decades. If I’m doing something for the press or media, it’s some longer reports or stories, because I work on one theme for several days. That theme is then treated in more detail. The whole instant manner of photography is not for me, that chaotic world where people are always running. Today, it is possible to do a lot with a good phone, there is less and less need for full-time photographers. There are more associates, while the agencies hold a monopoly and sell entire contingents. The author’s freelance photography is dying, but what I do is rare. I am lucky because I document things, I deal with social documentary photography that is not directly threatened by artificial intelligence. New and current things must be done by a person, not a program or application. I think there is a small hope in all of this, but I’m not a big optimist.