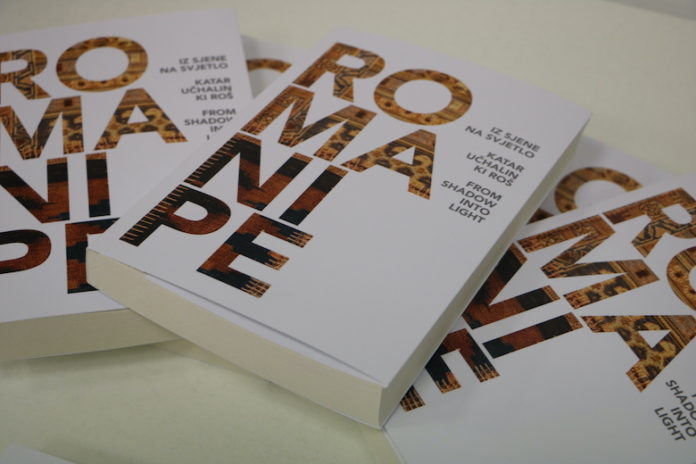

Recently, the Croatian Romani Union “KALI SARA” published the book ‘Romanipe, from shadow to light’, which brings ten narrative-journalistic stories about Romani men and women from Croatia and the region. The book’s editors, Maja Grubišić and Selma Pezerović (both also editors and journalists of Phralipen), came up with the idea for the book precisely through journalistic work and recognizing the stories that deserve to be expanded and published in a bound format.

As they said in the book’s foreword, in their many years of work on promoting Romani history and culture, they have always been most inspired by living stories of people who, despite difficult situations, persist in making their lives and the lives of others safer, better and happier. There are ten such stories, or ten people behind these stories, in the book ‘Romanipe’, which is currently a one of its kind publicist phenomenon in this area.

‘Romanipe’, the theme and title of the publication, signifies the overall Roma identity and spirit, and the art of living and survival is an important part of it, as well as the awareness of belonging to the Roma community, despite the many differences within it.

Orhan Galjuš, a journalist originally from Kosovo, who now lives in the Netherlands, writes about the Romani language in his story, reflecting upon how he anchored himself in it wherever he was in the world. Galjuš also reflects on the victory of the Roma spirit, which he recognizes in the fact that, although the Roma have been persecuted throughout history, they did not become persecutors themselves, and did not appropriate violence as their own path.

Elvis Kralj, who works as a teaching assistant for Romani children and a translator of fairy tales and stories into the Bayashi language, wrote an intimate confession about his childhood, his search for identity and the desire to belong. Kralj writes strikingly about the sense of guilt and responsibility that completely overwhelmed him as a child, and which he considered only his own for a long time, without trying to break it down into social factors.

The story of jounalist and translator Mirdita Saliu, who lives and works in Macedonia, is based on memories of working with Professor Shaip Yusuf, a translator and author of the first Romani grammar, who participated in both the Yugoslav and international Romani movements and was one of the organizers and participants of the First World Romani Congress.

He would call me in the evening, tell me what he had found, and I would go to him. By then, we were already living close by, both in the same settlement, as neighbors. “Let’s go to Uncle Shaip’s”, I would say, taking my son into my arms, writes Saliu.

Her story is a wonderful reminder of the importance of knowledge-sharing, supporting each other and inspiring without patronizing, always keeping in mind the common good and collective growth.

Translator and journalist Hedina Tahirović Sijerčić writes about the foreign land in which she is trying to find meaning. And that word refugee! How many more times will I hear that word in the years to come. In Bosnian, in Romani, in German, in English. Muhadzir, našado, flüchtling, refugee. In one word – alienation, writes Tahirović Sijerčić.

Apart from alienation, her story also branches into ownership, into memories of home, into nostalgia, but also (self)preservation through the recognition of her own knowledge, and the knowledge of those who helped her broaden it. One of them is certainly her father, about whom she writes how he did not allow her to knead pies and bread, but always encouraged her to study.

In her story, opera singer Nataša Tasić Knežević, the soprano and soloist of the Serbian National Theater’s Opera, recollects a cold winter evening at the club of the National Theater in Belgrade. At the time, she was talking to her colleague Predrag Gost, who asked her why she had not been trying to pursue a career in Novi Sad, to which she replied that she was sick of racists. Without missing a beat, Gosta immediately called the director of the Opera of the Serbian National Theater in Novi Sad and asked him if he was a racist. You are going to Novi Sad, they will listen to you sing. He said he was not a racist, was the message after the conversation. The rest, as they say, is history.

The book also features the story of Vedrana Šajn, the initiator and host of the only internet radio dedicated to national minorities, in which Šajn invested her entire dowry, and singled out her mother as the greatest supporter of her work.

In his story, writer Alija Krasnići introduces the world of his literary beginnings, the awakening of his desire to write. Krasnići, among other things, writes that journalist Rade Nešić, his literary group friend, proofread his works in Serbian so that members of other nations could understand his verses, which filled the pages of thicker and thicker notebooks. In 1984, Krasnići was admitted to the Association of Writers of Kosovo and Metohija as the only Romani member. I started writing and I never stopped, says Krasnići.

My story begins when I cross the bridge over the Vardar in Skopje. We lived in a Roma settlement, known as Topana, in the time of good Yugoslavia. This is how the actor and poet Neđo Osman writes about his settlement. It smelled of bread, the houses looked like Lego bricks, and after the great earthquake in which it disappeared, a new settlement, Šutka, was created for the Roma in Skopje. Osman also reveals to the readers how he first learned that he was a gypsyin elementary school. His acting career helped him in dealing with this cognition, in analyzing and changing it for himself and for the world.

The book also features Veljko Kajtazi’s story about the creative process behind the Romani-Croatian and Croatian-Romani dictionary, as well as the story of the thoughts and emotions of Edis Galushi during his performance of an authorial monodrama in the Romani language Panta Rei. The editors rightly pointed out that these ten stories open up a cathartic space for thinking about building a society that all of us will love more, a society that will be better for everyone.

One of the ways towards such a society, which is visible from this book, is that of mutual support, collective work and inspiration. In all of the stories, the authors recognized someone who gave them the wind in their backs, said a nice word, picked up the phone and asked a question which needed to be asked, walked with them, reviewed texts, and gave advice. Be it a mother or a father, a professor or a friend, a neighbor or a colleague at work. The greatest value of this book is that it shows how far we can go and how gently and powerfully we can create life when we are people towards and to each other.