In a conversation about peer violence, my interlocutors, psychology professors with extensive experience working with children and young people, agreed that peer violence has been on the rise in recent years. In addition to physical and verbal violence, electronic violence has become the most common form of violence today. One of the psychology professors has fifteen years of experience as a professional associate psychologist at an elementary school, while the other gained seven years of experience by working as a substitute psychologist in schools, at the Croatian Employment Institute, and later as a psychologist at the Center for Providing Assistance to Children and Young People with Developmental Risks, Developmental Deviations, and/or Developmental Difficulties.

There used to be more physical peer violence than there is today, when, alongside verbal violence, a whole range of new forms of violent behavior have emerged, collectively known as ‘cyberbullying‘ or, in Croatian, electronic violence, says a professional psychologist from an elementary school. She points out that this form of violence has increased significantly after the coronavirus pandemic and is also characterized by much greater cruelty because the perpetrator isolates themselves from direct contact with the victim. This way of carrying out violence allows the perpetrator to distance themselves from the victim, and there are numerous examples showing that the perpetrator does not retreat, does not give up. In years past, the facial expression or behavior of the victim would have stopped them, but now, the awareness of hurting another is just a thought that is not part of their cognition. Child perpetrators, precisely because of the lack of feedback on the other person’s reaction, feedback that is part of non-verbal communication, such as body language or tone of voice, often cannot understand the extent of the harm they are causing to others.

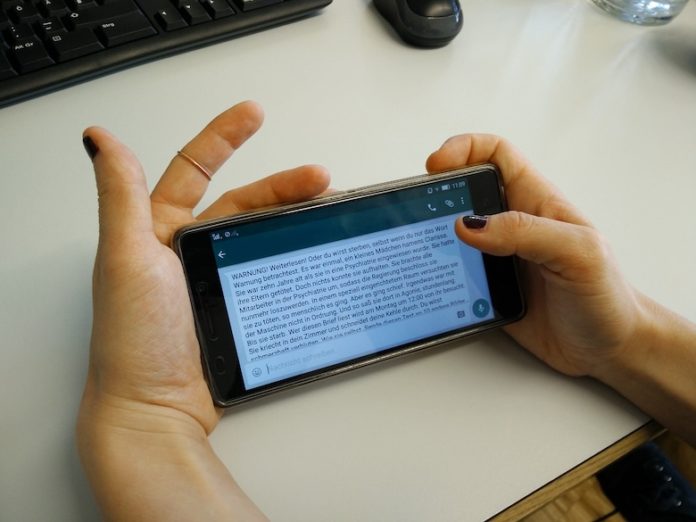

I believe that the emergence of electronic media has contributed to the increase in peer violence precisely because of the simplicity and accessibility of social networks, as well as other channels for directing messages, videos, or photos intended to harm another person, says the psychologist who provides assistance to children and young people at the Center. Perpetrators of electronic violence can often remain anonymous due to the possibility of hiding their identity or presenting themselves under a false name. Likewise, by spreading violence through electronic media, the perpetrator can gain the support of a larger group. It is particularly important to emphasize that any form of violence through electronic media leaves an intense mark, in the sense that the victim can read or see what another person has written or published about them several times. With each new reading or viewing, the pain is inflicted on them anew. In addition, e-violence can be present at any time, as long as the victim has access to a mobile phone or the Internet.

According to the experiences of the interviewees, boys are most often the perpetrators of physical violence, which includes, for example, pushing, hitting, and pulling. Both girls and boys participate equally in verbal violence, such as ridicule, insults, humiliation, and/or threats, while emotional violence, such as isolating and excluding a child from various groups and games, spreading lies and secrets, gossiping, and the like, is more common among girls. What is important to emphasize is that in cases of peer violence, both children, the bully and the victim, are actually victims of violence.

Child – Bully and/or victim

Based on my professional observations, victims are most often more withdrawn children, quieter and different in some way from their peers. They are often excellent pupils. Sometimes they may be more sensitive than other children and react more to provocations, says the school psychologist, concluding that there is always a difference in power between the bully and the victim – the bully is either physically or mentally stronger than the victim. Generally, in the eyes of the bully, the victim is always more helpless. I agree that it is often the case that these are withdrawn children. The reasons for this can be varied, including self-doubt, anxiety, or a tendency to depression, confirms the psychologist from the Center based on her experience. It is sometimes not possible to detect that a child is a victim of peer violence at the very beginning because victims do not decide to report such behavior immediately. The reasons are varied, from the lack of trust and belief that no one can help them, to not wanting to betray a friend and being a ‘tattletale’, to fear of being even more isolated from society, or simply feeling ashamed that someone will find out about it. I even had a case of peer violence in which, only after the violence occurred, it turned out that the bully had been a long-time victim. At one point, it became too much for him, and in that isolated case, he was violent toward his long-time bully, describes the school psychologist. She continues: As hard as it is to believe, in the period preceding it, there was nothing to conclude that he was suffering from violence. This is why we distinguish between violent behavior that is an isolated case and frequent violent behavior. In the first case, we can talk about children who were not problematic during their schooling and who, at one point, experience a change in behavior – such as aggressiveness in communication, impudence toward teachers and peers, which is the result of some change in the family or a situation they cannot cope with, such as illness or death of a close family member. Sometimes violent behavior is the result of a change that occurred earlier, remained unnoticed, and only later reached its culmination. On the other hand, in children in whom violent behavior is constantly present, it is most often due to a long-term inappropriate or dysfunctional family situation.

Through her experience working at the Center, the psychologist states that it is much easier when she can get to know the children better through regular work. It can be noticed that something is happening to the child if there are more noticeable signs, such as loss of appetite, sleep disorders, withdrawal, and/or various unspecified physical symptoms and pains, such as frequent stomach or headaches. Knowing the children involved in the work well, and who come to the Center once a week, makes it easier to monitor the child’s progress and provide encouragement and adequate support while considering the fears and doubts that prevent them from opening up. On the other hand, some victims can also show intense outbursts of anger and aggressive reactions toward others. We have had examples of children who continuously behaved aggressively toward another person in the group, for example, because of an unusual accent and/or language and speech difficulties. When we talked to them privately about such behavior, it was discovered that the bully in this case had experienced similar things in another environment, and was in the role of a victim there. In the Center where I work, the most common examples are bullies who were victims in other environments, such as in the family or at school. Some visible signs in these children include outbursts of anger, low tolerance for frustration, difficulty dealing with intense feelings, underdeveloped communication skills, and/or continuous attention-seeking behavior.

In practice, therefore, we often encounter violent children who have themselves been neglected and injured. Some have been victims of domestic violence or bullying by other children. Usually, such children have a need for attention, which, due to fragile self-esteem, often develops into a need to feel superior to others. Such children, whose basic social and emotional needs are not recognized or adequately met, may in the future adopt similar patterns of behavior to those they were exposed to in the past. It should be noted that this is not always the case, as there are many other factors that influence the occurrence of violent behavior in children.

The psychologist from the Center also highlights examples familiar to her in everyday practice, namely, cases of verbal and emotional violence among children with disabilities and/or certain developmental risks. These children often have behavioral patterns that make them prone to poor social interactions with peers or result in them making fewer friends than children without developmental disabilities. Because of their isolation and/or distrust of their environment, they report violence less frequently, making them ideal victims. When they establish a relationship of trust and open up, they mostly talk about verbal forms of peer violence and exclusion by peers, which can have serious consequences for them. Children exposed to such behaviors may feel sad, withdraw into themselves, or experience physical symptoms such as stomachaches or headaches. They may refuse, for example, to go to groups of children, to the playground or to birthday parties.

At the end of the conversation, the interviewees concluded that, although in recent years there has been more emphasis on the topic of peer violence than before, it seems that there is more of it than is actually being discussed. What also worries them, and which has increased significantly after the coronavirus pandemic, is the rise in internalized emotional disorders in children, such as depressive and suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, panic attacks, anxiety, and self-harm. The protection of children’s mental health is a long-standing problem that the Ombudsman for Children has repeatedly warned about. In her latest report, she states that mental health protection must be systematic and continuous throughout Croatia to prevent more serious problems and effectively respond to the need for hospitalization. Special attention should be paid to finding the causes of children’s mental health difficulties. Despite all the warnings, recommendations, and suggestions, there has been no progress in meeting the needs of children and young people.

Data on unmet needs is provided by expert psychologists and child psychiatrists, as well as by children who, in direct contact with experts, including the Office of the Ombudsman, point out that there is no one to provide them with appropriate professional assistance when they need it.

The publication of this text was supported by the Electronic Media Agency as part of the program to encourage journalistic excellence