Entering marriage before the age of eighteen is considered a violation of human rights regardless of gender. However, globally, child marriages in which girls are minors are prevailing, making up five-sixths of those, compared to only one-sixth of those in which boys are underage. This is due to the firmly established belief that men have significantly greater employment opportunities and that they are the ones providing for the family. In practice, this results in parents and families putting far greater pressure on girls and women to accept an early marriage as something normal, and the continuation of education as something irrelevant. In this way, they lose access to secondary and higher education, and thus the opportunity for future earnings and economic independence.

According to research by the World Bank, there is a shocking number of countries that have at least one law that treats women and men differently. Disgraceful is the data that in some countries marital rape is not considered a criminal offense. Furthermore, 49 countries do not have legal provisions to regulate domestic violence, while 45 countries have no legal provisions for sanctioning sexual harassment. Therefore, among the many inequalities that women inherently face, the abolition of the right to education, which is of course related to education being marginalized, seems just like another drop in the ocean of injustice.

The World Bank and the International Center for Research on Women recently conducted a study in 15 African countries, establishing a strong connection between the level of education achieved and child marriage, showing that each additional year of schooling significantly reduces the possibility of a girl marrying before while being underage, and consequently for. Therefore, they recognized the continuation of education as the most effective strategy for preventing child marriages. The results of the database research carried out in Croatia several years ago by the Office for Human Rights and the Rights of National Minorities and published in the book titled Uključivanje Roma u hrvatsko društvo – žene, djeca i mladi (Inclusion of Roma in Croatian Society – Women, Children, and Young) lead to the same conclusion, according to which 27 percent of Roma women who interrupt their education do that because of an early marriage, pregnancy, or parenthood.

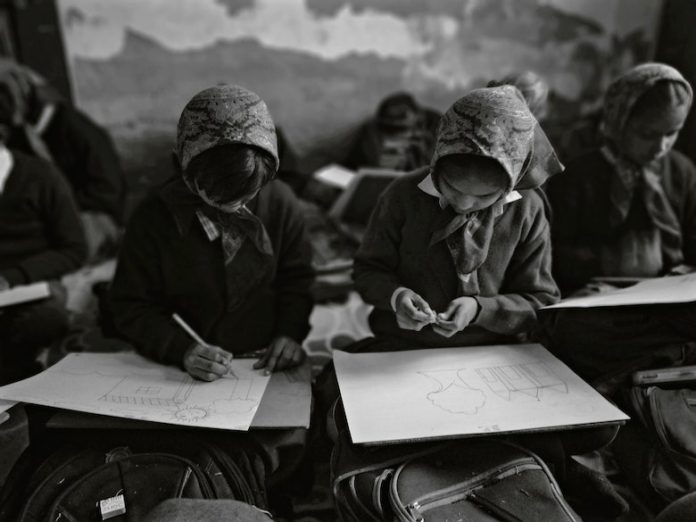

When a girl gets married or becomes pregnant, she is expected to drop out of school and take care of the house, children, and family as a wife and mother. The continuation of her education is in most cases impossible or much more difficult due to childcare and household chores, as well as the stigma and disapproval of the community that string along. Laura and Lea, members of the Roma national minority, who pursue education despite the community’s expectations talk about exactly such an experience. Their example sparks a change in the perception of their fellow citizens.

Laura lives in Zagreb but comes from a Roma settlement where education is often reduced to completing a few grades of elementary, so she never had the support of her family and community. She became pregnant at 15 and was expected to drop out of school. Only thanks to her persistence and good people who allowed her to study at home and come to school only to take exams, she managed to finish the eighth grade. When she decided to continue her education after giving birth to her daughter, the community started judging her. Education is not valued in my family. They think I am crazy. They could never accept that I don’t want to be a Roma woman who will give birth to many children, stay at home and make ends meet by begging or whatever, she says. For them, marriage is the pinnacle of life and it doesn’t matter at all whether the girl wants it or not and whether there is true love between her and her husband. This is especially true for my father’s side of the family, while the situation is a little better on my mother’s side, my mother never supported me getting educated. She never went to school, and my dad only completed four grades of elementary school, and what they learned from their parents they consider to be completely and utterly true. What their parents did to them, they are now doing to their children, and their children will do the same to their children in the future because this is the only way they know. That’s why I want to be an example to all those girls who, after the birth of their first child, give birth to a second, third, and so on and never stop to think of another life and other opportunities, which only their education can bring them, says Laura and states that her family does not understand her so they can neither support her nor praise her decisions.

Although just a child herself, Laura’s decision to keep her baby and take responsibility for another life growing inside her, and then to graduate from college one day, was firm from the very beginning. Today, at the age of 18, she is finishing high school and plans to study social work. She regularly participates in educational programs for young Roma organized by the Croatian Romani Union “KALI SARA”. Moreover, she was one of the most active participants in the workshops on communication skills, as well as on the topic of public policy advocacy. However, her own family ostracized her because of her decisions. They consider it unnatural that she is 18 years old and has only one child. Because of it, she only visits her neighborhood where she has lived since birth when there is a death in the family. For all the insults I heard during my last visit, I told them this: ‘Just keep on saying I’m a fool, but I’m smarter than any of you. No one has finished more than four grades of elementary school, and look where I am! I will never stop educating myself and people will respect me.’

Prejudices and judgments of the community are not something unusual for her or many other Roma women. During her pregnancy, the medical staff insulted her at almost every checkup. I remember lying on the examination table and the doctor yelling at me. He asked what was wrong with me, whether I had ever heard of protection, and how, as a minor, I was coming unaccompanied. He also threatened to call the police, and I was either on the verge of tears or I cried quietly. After one check-up, I even called the hospital’s manager to complain, but he replied that he could not help me. The same continued after the birth when I took my baby to the pediatrician. There, they regularly addressed me as Osmanovićka and laughed at me saying that I would give birth to ten more, even though I told them that I planned to continue my schooling. I understand that there are Roma women who give birth as minors and who have many children, but it would be nice if they managed to say a few words of support instead of mocking me.

The resistance I faced when I decided to continue my education was unbelievable, says Lea Oršuš, citing a similar experience. Today Lea is a second-year student of social work at the Faculty of Law in Zagreb, who passes all exams on time and regularly enrolls year after year. For four years, almost every weekend and holiday that I spent with my family, I explained to them the essence and purpose of my education, because enrolling in high school, after which I have no real vocation or profession, was the source of their enormous opposition. It was somewhat clear to me that they wanted me to become independent as soon as possible and have my own life, and the path I chose seemed difficult and complicated to them. During all six years of my high school and college, they offered me a way out of what they thought was a senseless running after deadlines, finding me jobs and even opportunities to go abroad, but no matter how tempting and promising these offers were sometimes, they were never an acceptable option. I firmly decided to finish college, to show everyone, but primarily myself, that there is a world outside of the Roma settlement and that what we see on television can become our reality. Such a decision coming from a girl was incomprehensible because education, even at the lowest level, is still a boys’ privilege. The rebellious women among us, whose indestructible spark of imagination allowed us to see ourselves as being employed, in companies i.e. Rimac Automobili, did not give up our decisions, bringing our experiences back to our families and settlements. Many young people see them as role models. Being persistent they began to change their parents’ attitudes who encourage their younger children to follow in the footsteps of their older brothers and sisters.

If I had stayed in the settlement and given up my education, I would have already had two children by now, with the third probably on its way, says Laura. It is also possible that I would suffer domestic abuse by my husband, as my grandmother still suffers to this day, whom my grandfather beats even after forty years of marriage. While I was in the safe house for youth operated by Caritas with my baby, waiting to turn 16, there were several other Roma girls my age, who shared the floor with me. They didn’t even think about finishing school. Later I found out that some of them had their children taken away because they did not take care of them, others returned to the settlement to live with their husbands. Among them was a young Roma woman who had two more children and who, even though her husband beats her, does not think she can have a better or different life.

Laura married her child’s father at the age of 18 and is overjoyed that he supports her in continuing her education and realizing her dream. In this story, she is the protagonist, a successful young woman who was condemned by her own family, and in front of whom she will stand one day, seeing the disbelief in their eyes, caused by her achievements. I would like all those who generalize Roma women, thinking and saying that we are all the same and that it is okay to insult and condemn us, to understand that there are those among us who bring changes to their community and that it would be a right thing to support us, concludes Laura.

Nevertheless, Romani women do not give up their national identity, says Lea and points out that thanks to their example the awareness of the need for education is spreading in the Romani community. So to participate in a process that, by determining clear values, such as the benefits brought by the acquisition of knowledge and a high level of education, personal prosperity, dignity, economic independence, and freedom, leads to social progress and the development of all social groups, Lea got actively involved in the implementation of the project Educated Roma Women – Empowered Roma Communities!

The education of a high percentage of girls will likely have an intergenerational effect and girls whose mothers are educated will be at a significantly lower risk of marrying at a very young age, as stated in the World Bank’s 2018 report Missed Opportunities: The High Cost of Not Educating Girls.

The driving forces of social change in terms of continued education and family planning in later life exist within the Roma community itself, and young Roma women who have decided to continue their education despite all obstacles, as well as educated Roma women, are a significant part of it.