We always arrive to the agreed-upon place too early. This is a somewhat good feature, but when the weather is cool and the agreed-upon place out in the open, then we think it’s a ‘disease’, as well as being late, because it would be nice to sit in the warmth of our home a bit longer and still arrive on time. We are still driven by enthusiasm as the fundamental motive for working in the Phralipen editorial office, so meetings in one of the gardens of city cafes seem like a coffee break in free time at first glance, but then soon the table becomes cluttered with piles of paper listing texts for the portal, topics for future magazine issues, reports and statistics. Then come the various thoughts and ideas that we share with each other, springing from the imagination inspired by the living stories of people we have worked with over the years. These stories are part of their memories, most often colored by deep emotions due to the injustices experienced as a result of the fact that society perceived them as others and different.

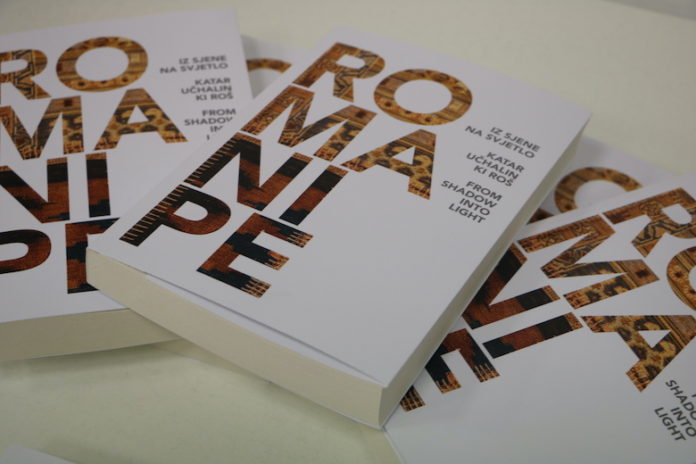

The strength of their spirit and the perseverance in making their lives and the lives of their compatriots safer, better and happier, while emphasizing our common qualities and the human values we share, are always the underlying motivation for us to re-examine our own beliefs and aspirations. Somewhere in these truths, a spark for combining their stories into a collection that will be of interest to a wider readership was lit. This spark lingered for several more years during our joint work, in which we were undoubtedly connected by the Roma people until the narrative-journalistic stories written and united in the ‘Romanipe – From Shadow into Light’ collection received their printed form.

Published by the Union in the Republic of Croatia “KALI SARA”, the book was presented to the Zagreb audience in November this year in the presence of some of its authors – Alija Krasnići, one of the most prolific Romani writers and poets behind whom lies fifty years of literary work, and who states in his verses that “to believe in my verses you need to live my life”, the one inscribed with all the misery and poverty of the Roma people, the injustice and suffering, but also with everyday life in the settlement, youth, song, and love. Orhan Galjuš, a journalist and radio reporter, and a world traveler who, like a chronologist, records the history of his people, also arrived in Zagreb. He was joined by Veljko Kajtazi, who, although not a linguist by profession, united the Roma community in strengthening its identity by persistently collecting Romani words for many years, and finally uniting them in the first Romani-Croatian and Croatian-Romani dictionary. Also in presence was Elvis Kralj, an author who returned to his childhood in his story, remembering well what he was going through and how he wanted to be anything but a Roma, anything but the one they mocked and called derogatory names. Still, this experience, among other things, enabled him to better understand Romani children and youth and prompted him to work as a teaching assistant at the Pribislavec primary school in Međimurje for twenty years.

Some of the narrators who could not travel to Zagreb for the launch of this collection of stories sent their video message, such as Neđo Osman, a great Romani actor who had a strategy of his own throughout life, and which he shared with us during one of our previous meetings: “In various environments and situations, I kept saying I was a Roma, even when no one even asked me. I kept talking about the Roma even when no one cared, I talked so that others wouldn’t”. Greetings and regards were also sent by Edis Galushi, a linguist and actor, who relies on literature and theater to conveys his understanding of linguistic diversity as a true wealth of humanity and not as a means of separating people, as is often interpreted in practice. He examines the approach towards the Roma and tries to correct misconceptions with logical conclusions and emotions he arouses in readers and viewers, and when asked why does he do it, he replies: “For love, for family, I owe it to my ancestors, to my daughter, to all future members of our family, but also to myself”.

Women’s topics and identity

Stories by female authors, members of the Roma community in which women continue to position themselves, add value to this book because they not only changed things within the community by leading through example, but also changed the culturally conditioned perception of women both inside and outside their community.

The stories of these authors are in fact their intimate confessions about the moments in their lives that marked them and influenced their further work. In her story, Hedina Tahirović-Sijerčić speaks out about seeking refuge and life abroad, about tears, fear and unrest due to the uncertainty lying behind the word ‘refugee’. “How many more times will I hear that word in the years to come?”, she wonders. Mirdita Saliu, also a featured author, shared her experiences and memories of working with Shaip Yusuf, aware that she was one of the few who had the honor to learn from this prominent fighter for the affirmation of Romani identity, author of the first Romani grammar, initiator of the first television programs in the Romani language, teacher and mentor of the first journalists in Romani newsrooms in Macedonia. Vedrana Šajn‘s story began with a dowry, the one that, by marriage, a girl brings to a new house, and which she used to start her own radio, while the story of Nataša Tasić Knežević about the peak of an opera diva, began with an uncertainty that deeply permeated every single one of her cells for a long time because of negative experiences of fighting prejudice and racism. They were expected to know their place and accept the role intended for them, but they had different ideas.

“In the Roma patriarchal environment, the concept of gender roles and relations is common. Thus, in the Roma tradition, a woman’s place and role in the family was exactly known – what obligations she had to fulfill, what she was not allowed to do and what it was not her business to start. The Romani woman is thus subordinate to male family members, especially the elderly”, said Mirdita Saliu, adding: “That is why we say that women are doubly discriminated against – first in their own home, and then outside of it, from access to services to public life. Fortunately, that is slowly changing, too, and being left in the past. New generations of Romani women are slowly but surely realizing that there are other roles besides the family one”.

In recent years, although still in small numbers, Romani women are becoming more visible in various areas of social and cultural life so they can, for example, be seen as authors of certain publications, which is without doubt a step out of the traditional framework. “This means that Romani women are still in the educational process, and I personally expect this current situation to change faster, considering new female names in literature”, explains Saliu, and asks: “If we express ourselves best in our native language, then why do we hesitate? Why don’t we do more to preserve that language and why don’t we use it enough in everyday communication?” Language is a living matter that is constantly evolving, so that also applies to the Romani language, which Saliu learned really well alongside Professor Shaip Jusuf and applied her knowledge every day. “Working with Professor Yusuf, who inspired me for the story Self-Portrait in Memory with which I partake in this collection, led me to learn about the long journeys of the Roma, their way of life, their way of expressing sadness and joy through songs and stories, many of which, unfortunately, remain only as part of the collective memory. This was precisely the reason for my dedication to journalistic research of my own people, which resulted in the publication of scientific studies on the Roma community and its suffering throughout history. In these studies, the gender component also plays an important role in various contexts in which attitudes towards women, stereotypes and discrimination are presented”.

Vedrana Šajn from Pitomača, the founder and host of the first internet radio dedicated to national minorities in Croatia, also agreed with Mirdita Saliu’s claims. Growing up in a Romani family, she learned to nurture traditional values and customs from an early age, among which completing primary school was considered sufficient education for a girl. Nevertheless, she decided to enroll in high school and then continue to pursue her education in college, and her parents supported her. “Being a woman in the Roma world, and especially in the men’s world, and I include the radio space as part of that world, is a little harder. Although women mostly appear as editors, most radio owners are still men”, says Šajn, who chose precisely radio as a medium through which to prove her abilities as a woman and a member of a national minority. Šajn also speaks about these experiences in her story titled First and female, which can be found in the ‘Romanipe – From Shadow into Light’ collection. “I am happy that my story found its place in the book, alongside those whose experience is as long as my whole life, it is a great privilege. Also, other girls my age are already married and have children, and I chose a career. This does not mean that I do not want a family, one does not exclude the other, but to create something with someone else I wanted to first create something with myself, to connect with and find myself inside. In the Roma community, it is still very common that as a woman, you are in charge of raising children and household chores, which are in themselves unpaid. This does not apply to the work with which you earn a living, and especially not for my job because it is specific, it requires flexibility, an open mind and understanding. “From my parents’ example, it is clear that my mother is the one who has always supported me, and she still does today and attends all events with me and can identify with me, while my father is always on the sidelines, providing silent support”.

Much like the radio, the theater is a very well-organized mechanism that requires daily engagement, and Nataša Tasić Knežević, an opera diva from Serbia, knows this best. “I often thought about the mere fact that life is really unpredictable, and about its cyclical movement in which after every major problem comes a solution, if the person is ready for it. At that moment while I was waiting for a meeting in the club of the National Theater, I felt ready for change”, explains Tasić Knežević and further recalls: “When someone is perceived as different, it takes a lot of work and proof to ‘justify’ their presence, which, in my case, was in the theater”, she says, cautiously hesitating to reduce such actions to the notion of institutional racism. It is important to create opportunities for the Roma, but also for every other minority group to progress and mature in the field of art, but also the art world, as equal members of society, and that its members are not seen as second-class citizens, but only as people with their full potentials.

For a long time Tasić Knežević was faced with her greatest insecurity, which was manifested in self-doubt and it took a lot of effort and self-awareness to understand where this insecurity comes from, why does she feel the need to repeatedly listen over her own performances in preparation for opera roles assigned to her. Although this insecurity is not uncommon to artists, as she herself states, in her case, it was additionally permeated with negative experiences due to her Romani origin. Her neighbor Milica, a psychologist who works with the homeless, and with whom Nataša is very close and sees her every day, at least on long walks with dogs, helped her to come to this realization. “One day, Milica asked me what I would say to the person who hurt me, as if they were sitting across from me now, in this moment, in this place. I watched Lea and Medo dragging a branch and playing, then started crying, told her what was on my mind and felt great relief. Sitting on a hill with Milica and watching the dogs, I set my soul free”.

Tasić Knežević emphasizes that women are always in the shadows, so the moment they step into the light is an important one that can change a lot, but in the end we are still shaped by life experiences, so we need to listen in, notice and accept good opportunities. “There is one scene that also repeats itself in my story, in which Margaret from the Faust opera stands in the church and says: “Lord, allow your humble maid to kneel before you”, and at that moment Mephisto appears. In every temple, be it a religious or an artistic one, you have a divine and a demonic side, and a choice, you have good counselors and bad ones, so I must say that I have brought my entire prayer side into two roles in my life, and those are the aforementioned Margaret from the Faust opera and Micaëla from the Carmen opera. Both of them prayed and overcame the bad, but through sweat and tears, bleeding extremely sincerely from their hearts. Did that bring me relief? No, not at all, but it helped me to put on a smile and some red lipstick, to cover up my extra weight and move on through the streets of our wonderful world”.

Leading by example, by graduating, securing employment and independence, Hedina Tahirović-Sijerčić changed the perception of the Romani women in her neighborhood, but her planning for the future was interrupted by the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina which erased all her plans, took away all security and brought restlessness and fear into her daily rhythm of life. Overnight, she was left without the opportunity to work and provide for her family and was forced to go to Germany with her two children. She described the days spent in exile in her story titled Alienation, recalling how she started working on her first poems in a small container room in a German town.

Years later, Tahirović-Sijerčić created an analysis of women’s literature and writing among Romani women in the historiography of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The history of Yugoslav literature testifies, as Tahirović-Sijerčić also argues in her book titled Gender Identities in the Literature of Romani Women Authors in the Former Yugoslavia, that women’s creativity was not recognized, making female Romani authors additionally subordinated on the bases of both their gender and their nationality, resulting in insufficient recognition and undervaluation of Romani women’s literary tradition. Finding a place for Romani women in Romani literature is generally very difficult, Tahirović-Sijerčić further argues, explaining that they were not excluded from the stereotype and prejudice patterns used to create “otherness” by the more dominant and powerful groups, but also by members of their own Romani people, because these women did not fit into the traditional and cultural patterns of Romani families or groups.

Continuing with her analysis, Tahirović-Sijerčić argues: “In terms of the common experience shared among Romani women authors who are excluded from women’s creativity and women’s subculture by feminist criticism and gynocriticism, I think about their, I would argue, subculture within a subculture. In this context, as well as in the one of male Romani creativity, female Romani authors are ‘others to the others’, but, as I argue in my thesis, this ‘otherness of otherness’ and the ‘otherness’ created by Others is more bearable than the ‘otherness’ of the Other created within one’s own people”.

Deeply rooted patriarchy, the awareness of preserving that which is paternal, as well as customs and culture often find itself as themes of Romani women’s literature, which also displays history and how it changes throughout time. “By all accounts, themes in Romani women’s literature did not move far from the one passed down from generation to generation, and which falls under the category of folk literature with motives such as path, child, father and love, but has taken on a different, more modern expression established by the changes and developments of the languages of the majority nations”. It was precisely the unique use of the Romani language that enabled and created the history of the Romani written word and the beginning of Romani writing, within which Romani women often assumed the role of the “guardians” of the Romani language, passing it on from one generation to another by raising children.

A walk through life in one room

When discussing literature, it is definitely worth mentioning the worrying data on the illiteracy of Romani women, which is – according to the Office for Human Rights and the Rights of National Minorities of the Republic of Croatia – almost 2.5 times higher than the illiteracy of Romani men (7%). Furthermore, the data shows that the share of illiterate women is significantly declining among the younger generations, but a gender gap in illiteracy still persists in all generations. The big discrepancy between women belonging to the Roma national minority and the majority population is the data on the illiteracy of Romani women, who are more illiterate than women in the general population, but also than male members of the Roma community. This situation is partly due to the isolation of the Roma community, as described in the book review by prof. dr. sc. Ljatif Demir: the consequences of living in a lonely world “without a mirror in which others can also be seen, a living space without megalomaniac buildings that they did not choose themselves but in which they were isolated by those more powerful than them”. He further explains that the protagonists of the stories united in the collection are precisely those “who, having moved from that one room to one worldly room, took their own stories with them and then wrote them down. In them, they presented their reality, portraying existing Romani men and women who are not fictional characters”. With their indestructible spirit and creative energy, they turned disappointment into encouragement, fear into courage, and defeat into victory.

They give us insights into how we can all be better people together, how we should take care of each other, strive for mutual understanding and create relationships of cooperation and friendship, and we often talked about this in meetings held in the tranquility of one of the city gardens. The knowledge of the richness of the world in our diversity and empathy should be built into the foundations of any society that strives for humanity and the peaceful development of human coexistence in harmony with nature. Friendship is also built on such foundations, and this book was, among other things, created out of it.

The text was published on the Booksa portal as part of the project ‘And this is a question of culture?’ and it is based on conversations between Selma Pezerović and Maja Grubišić with some of the narrators of the book ‘Romanipe – From Shadow into Light’, which they also edited.