Daniel Baker is an artist and curator who lives and works in London. He holds a Ph.D. on Roma aesthetics from the Royal College of Art, London. His work has been included in documenta fifteen and Manifesta 14, and has been featured in four editions of the Venice Biennale, both as artist and also as curator of FUTUROMA in 2019. Baker’s publications include WE ROMA: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art, Ex Libris, and FUTUROMA, and his work is exhibited internationally and can be found in collections worldwide. Baker’s work examines the role of art in the enactment of social agency via the reconfiguration of aspects of Gypsy visuality.

When you look back on the years leading up to your studies at the Royal College of Art in London, what do you see? In what way is your personal and professional development intertwined and how does this reflect on your art creation?

I am the youngest child of a family of Romani Gypsies. The Romani encampment that we lived on was sold for development by the owner in the 1950s and a number of the families were offered housing in a street overlooking the site that they had previously inhabited. This meant that the community remained relatively intact despite the disappearance of the main encampment. My family is part of the large population of Romani Gypsies that have lived in and around Kent, in the southeast of England, for many generations. Most live in houses now but many still live on caravan sites in the area.

I enjoyed drawing from an early age and I got better with practice. My family was always making things at home like paper flowers to sell. My father would make flowers from wood, too. These early experiences of domestic social artistic practice have continued to be influential both in my work as an artist and as a curator, and theoretician. My family encouraged my interest in painting and drawing. Visual culture is taken very seriously amongst Romanies and any skill in relation to this is highly prized. This is perhaps partly due to the fact that visual communication is so important in Romani and Traveller groups given our historic lack of attachment to the written word. For example, we had no books at home when I was a child. Our histories didn’t seem to be contained within books so books were not seen as important.

As a visual artist, my main area of expertise has focused on sites of knowledge outside of the written word. Sites where the construction and distribution of meaning are primarily reliant upon sensory stimuli, and played out via visual, performative, and experiential means. My interest in aesthetics is influenced by and has been echoed within, Romani culture, where, in the absence of a literary tradition, material culture, performativity, and oral histories have acted as the engines of Roma Knowledge. In an environment where literacy is not commonplace, and where the written word is widely mistrusted, it makes sense to communicate – and to acculturate, by alternative means.

How did you first enter the art world? Were you trained and who are your inspirations?

After completing my formal education, I attended Art School from the age of 17 to 21, where I studied contemporary art practice in all its forms, becoming immersed in its conventions. My time at art school was spent trying to work out how I fit into the Western art canon by experimenting with a variety of voices before I began to understand that the preoccupations within my work, and in my life, did not fit so easily into the received art narrative. After some years of searching and trying to develop my own voice, a shift came with the realization that my visual references and aesthetic vocabulary were grounded in the surroundings in which I grew up, primarily influenced by my Romani family and my Gypsy culture. It wasn’t until my late thirties, after studying for a Master’s degree in sociology, that I began to concentrate on a particular set of concerns within my work. This is when a personal style began to take shape and I began to consciously operate from my Romani subjectivity.

My work became grounded in the visuality of Romani culture, an interest that emerged during the completion of my MA dissertation in 2001, which examined the experience of LGBTQ+ Romani people across the United Kingdom, titled ‘The Queer Gypsy’. My research was the first conducted on this subject worldwide, and as such no literature existed for me to draw upon other than that relating to other intersectional communities. My research was concerned with Roma (in)visibility; focusing on the possibility that the identities in question (queer and Romani) may not immediately be signaled by physical appearance (or bodies), and that this allows a heightened opportunity to manipulate, or shape, identity according to location and situation. It also examined the phenomenon of ‘passing’ – of being able to conceal or reveal particular aspects of identity (ethnicity and sexuality for example), depending on context and the potential benefits (safety from harm etc.).

The illusive questions of (in)visibility which had impacted so very significantly upon the lives of those people that I interviewed, prompted in me a desire to examine wider questions of visibility for Roma and the ways in which Roma visuality continues to influence the lives of Roma people today. My sociological research experience combined with my art training meant that I began to look at Romani visuality in a different way, and its meanings began to gradually influence the work that I was making. Consequently, issues of visibility, and the paradoxes of revelation and concealment, became important themes as I developed my multi-sited methodology of art practice within the doctoral program at the Royal College of Art. My PhD thesis titled ‘Gypsy Visuality’ was the first time that the concept of Roma aesthetics was introduced into the discourse. As I began my research at the RCA, I was approached to be involved in the first Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007, where I acted as an exhibitor and advisor. As I approached the end of my doctoral research, I was invited to be involved with the second Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which was mounted in 2011, again as an exhibitor and advisor. My experience of being involved in these early Venice projects proved invaluable for my research and also led to a wider interest in my work as an artist.

What would you single out from your childhood, some phenomena or objects, which you later realized became the subject of your art? To what extent can the recontextualization of existing phenomena and symbols within the framework of art enable the emergence of new interpretations that could then question existing ideas?

I am directly influenced by the interior décor that my family would surround themselves with during my childhood. In our home, and in the homes of our wider community, glittering menageries of glass and porcelain animals would vie for space with gilded plates and decorated mirrors to satisfy what seemed to be the common appetite for the opulent and the exotic. Objects of desire were often displayed on shelves in cabinets made of ornamented glass with mirrored panels which would show multiple reflections of the treasures in disorientating kaleidoscopic illusion. The recurrence of qualities like reflection and shininess within my work shows the lasting impact of my domestic environment upon me, my thinking, and my art practice methodology.

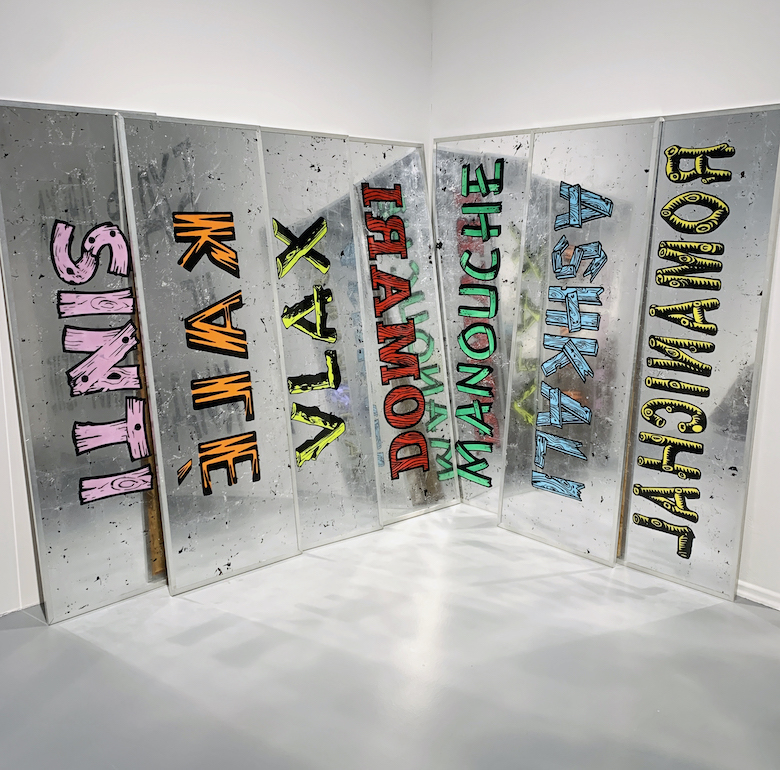

I use the device of the decorated mirror and the fracturing effects of reflection to examine ideas of revelation and concealment and the simultaneity of display and occlusion; elements which I consider to underpin Roma culture historically. The unexpected use of motifs can also generate new interpretations of existing phenomena. Here I refer to the juxtapositions of defacement and ornamentally which I have employed in my ‘Looking Glass’ works. In this series, marks of destruction collide with ornamental motifs within a mirrored ground. The layered oppositional qualities used throughout the works can be seen as a reflection upon the historic roles that Roma continues to perform in the popular imagination – both the romantic and the demonized. Questions regarding the relationship between vandalism and embellishment raised by the works, along with their concurrent duality of function and ornament, add to the ambiguity of these objects and their potential to encourage the viewer to think about familiar images and tropes in new ways.

I have always been interested in vernacular forms of cultural production. More specifically objects that form the fabric of our everyday lives and that are often overlooked, a devaluation that renders these and cultural artifacts like them invisible. Modes of production employed to create these objects are similarly devalued, especially in the art world. Part of the intention of my work is to invite the viewer to consider again objects, processes, and themes that seem to inhabit a previously overlooked field of production. Objects that may have been understood in a particular way can be re-encountered to illuminate their function as art objects and perhaps expand the meanings that they convey. This theme in my work relates specifically to questions about the relationship between marginal artistic practices and those that form the elite center ground. Such questions are important for me and act as a way of thinking about the relationships between marginalized peoples and the supposed mainstream society.

My art practice is eclectic. This consciously reflects Romani style and the way that our community has drawn upon many influences throughout our historic migratory journey across Asia and Europe. My father was a scrap metal dealer so the activity of recycling and making something new from things that might be thought to have reached the end of their useful life is also a continuing theme; taking familiar things and using them in new ways in order to re-activate them and the stories that they can tell us.

The rich visual culture of the Roma community, as well as its influence, are your inspiration. The Roma influenced European art, and yet art as an instrument was often in the role of colonization and stereotypical representation of the Roma – the most numerous European minority.

The concept of the ‘artist’ is based upon the image and the lifestyle of the Roma, and this is well documented. Yet, the fact that we are responsible for the very idea of the contemporary artist that continues to dominate cultural narratives today, is regularly overlooked. A reminder of the origins of the concept of bohemianism is relevant because it gives us a way of articulating and quantifying the value of Roma culture and of Roma people. It also offers a counter-narrative to the ‘Roma problem’; thereby perhaps increasing the possibilities for emancipation and equality.

During the emergence of the nineteenth-century intellectual elite, experimental movements copied the Gypsy style in a stand against convention. It was not any singular artistic activity that they sought to invoke but a way of life suffused with creative action, energy, and resistance. These aspirational qualities were signified primarily by the adoption of a ‘look’—a sartorial style that spoke concisely of a rebellious non-conformity, and at the same time embodied ideas of life lived on the margins of society. This potent shorthand for cultural rebellion has continued to endure long after its roots in Roma life have been obscured. Nevertheless, it continues to provide a viewpoint from which the intellectual vanguard can analyze and critique the status quo.

That the trope of the Bohemian still acts as a model for the popular image of the artist today is not without reason. Artists continue to occupy a liminal position within society—as do the Roma. Society is conflicted regarding the role of artists – likewise with Roma. Society tolerates artists because of their eventual worth but resents their flouting of the rules. The Roma are similarly resented – but their worth has remained obscured through the relative absence of any formalized material legacy. This situation, however, is beginning to change as today’s Roma prove that we can again inspire much-needed cultural and social reorientation, through actions like the appearance of artists of Roma origin at the most prestigious international contemporary art events, not as tokenistic symbols but because the work that they are producing has important things to say about society and the way we live today.

Although the intersection of gender, ethnicity, and race is also reflected in the art world, many artists of Roma origin do not want to characterize their art as exclusively and only “Roma” and consequently do not prefer to be presented as “Roma” artists, which you have also mentioned on several occasions.

I understand the ambivalence with being categorized as a Roma artist. It is something that I have thought about a lot. There are many parallels with discussions around the idea of Roma art which surfaced during the emergence of the current phase in contemporary art in which Roma began to be represented, namely the first Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007. The idea of Roma art was, and remains, complex, and any fixed notion of the category remains problematic. I used to be opposed to the idea of Roma art, preferring to describe a set of preoccupations and qualities that form a Roma aesthetic, and this remains the basis of my practice as an artist and curator. Thinking in these terms seems more realistic and certainly less restrictive and this is how I continue to link the various art practices that occur throughout Roma culture, not just in the Roma art world. That said I also understand the need for a snappier descriptor like Roma art, not least to form a central motif around which to mobilize politically and socially, but also for some art critics, art historians, and anthropologists to promote ideas and make assessments and value judgments, which they inevitably will.

The first Roma Pavilion helped to shift ideas about Roma beyond the historic notion of a culture in constant crisis. A new interest was brought about by a conscious attempt by Roma to present new narratives about our community through art. This re-presentation of Roma has helped precipitate a re-evaluation of our culture and perhaps it was inevitable that a label would be applied to the collective creative output of our community. There was always a danger that the pavilion could be seen as presenting an idea of ‘Roma art’ as fixed but this has proved not to be the case.

The same goes for the idea of the Roma artist. The category can be useful in some contexts (like applying for Roma projects) but is only ever one aspect of an artist’s identity. When artists who have enjoyed exposure through Roma projects seek to unlink from such associations, it can be seen as contradictory. Does the artist think that their product will somehow be devalued, or do they see themselves as having moved beyond the confines of such associations? It is a complex issue. I would say that it is completely understandable for artists to want to be recognized by the widest possible audience and in the broadest context, and many will be. But it is also important to lend support in sensitive and productive ways to the structures and communities which have supported us along the way.

You participated as a curator and exhibitor at several editions of the Venice Biennale. Last year, artworks were again presented to the audience at that international festival through the Roma pavilion. How do you compare, in the context of time, from the first Roma pavilion in 2007, when you started, to the one held last year, have the contents and ideas changed and developed?

The five iterations of Roma’s presence at the Venice Biennale have formed a logical trajectory it seems to me. Each has built upon previous appearances to broaden the themes, the inclusivity, and the reach of Roma representation.

The first, ‘Paradise Lost’ (2007), established a direct intervention within the art world through its very presence at the Venice Biennale, and its effect on international Roma political and cultural discourse was significant. It proved to be a catalyst by committing to a truly international approach to Roma contemporary art. The impact of the project cannot be overestimated in establishing the foundation for the current flowering of Roma artistic practice and its increasing influence within international contemporary art discourse.

The second, ‘Call the Witness’ (2011), called upon artists to bear witness to Roma communities’ struggles, through works of art, within the framework of the traditional Roma forum for conflict resolution, the Kris-Romani. By including both Roma and non-Roma artists and thinkers the resulting series of events highlighted the interconnectedness across art forms and ethnicities, and as such introduced a discursive and multidisciplinary dimension to the debate.

The third, ‘FutuRoma’ (2019), looked to the future for Roma by drawing upon aspects of Afrofuturism. The project offered re-interpretations of the traditional and the futuristic in order to critique the current moment for the Roma people. In confronting inequality through Roma subjectivities this project chimed with global contemporary art initiatives by emphasizing the emancipatory power of recognizing the transcendent power within the culturally specific.

The fourth (2022) took the form of a solo voice within a contextualizing choir. ‘The Abduction from the Seraglio, accompanied by Roma Women: Performative Strategies of Resistance’, reflected upon the themes from the titular story through a multidisciplinary approach. The project challenged patriarchal projections through a series of interventions, actions, and performances, to reflect upon the double minority position that Roma women occupy.

The fifth (2022), ‘Re-enchanting the World’, achieved what many had only dreamed of; a Roma artist representing a European nation at the Biennale. This was certainly a great step forward for Roma contemporary art, Roma recognition, and for Roma people. As Roma organizations continue to lobby toward a permanent home for Roma at the Venice Biennale the inclusion of one of our great cultural producers in the elite Giardini setting was a most welcome boost.

In summary, I would say that the trajectory of Roma’s presence at the Venice Biennale seems to have been an organic progression in that each iteration has succeeded in broadening the scope and the reach of Roma’s representation to an international audience. This has also opened up opportunities for artists of Roma origin and the subject of Roma within other significant international contemporary art events. Even though such rarefied environments may seem remote from the day-to-day situation for Roma on the ground, they are also where social attitudes and government policy can be influenced, and international perceptions persuaded toward alternative points of view, and as such remain important arenas for Roma participation.

Appearing and actively participating in major festivals and biennials are certainly a significant step for contemporary (Roma) art and culture, which, by being on the international stage, says that Roma also creates the European landscape. Despite the fact that art is more accessible than ever, its competition is intense, and often dictated by the rules of the country’s economic profit. How do you see it and do you think that the international art world is (sometimes) elitist?

The contemporary art world, including the market and major institutions, is turning to ethnic inclusion rather late in the day, and only now because their hand has been forced by the seismic events triggered by the Black Lives Matters movement. Diversity within the art world helps to build alliances across like-minded organizations. It also represents an augmentation of contemporary art discourse in terms of participation in the true sense. As such Roma’s presence on the international art stage not only contributes to the preservation of Roma cultural capital, it can also promote narratives that can be influential in changing attitudes.

At the heart of my practice as an artist and as a curator is a preoccupation with the role of art in affecting change. One of the ways that art can effect change is by showing us the value of that which is overlooked. When we are encouraged to look again at objects and ideas that have become obscured, we are encouraged to look again at the people that have generated them. In this way, the artwork acts as an extension of the artist which in turn acts as an extension of their community. By re-evaluating such objects, we are motivated to re-evaluate their makers and therefore the cultures from which they emerge. By re-evaluating and repositioning artworks and artists from diverse communities, the art world can achieve greater inclusion and representation; something which should be top of their agenda.

The absence of diversity within contemporary art discourse is mirrored within art institutions and state collections. The art world is a cumbersome entity that often trails behind other more immediate cultural instruments in reflecting, and mediating, inequalities within society. Consequently, the contemporary state of play is often slow to be mirrored within contemporary art networks – indicating a reluctance to look beyond the customary circuits of galleries, art fairs, and biennales to find fresh approaches. Relying upon a limited range of influence and opinion may suit the reliably market-led art world but it will not necessarily reflect the range, or quality, of work being produced at any given time. This is why Roma’s presence at top international events like the Venice Biennale, documenta fifteen, and Manifesta 14, which all included significant Roma projects in 2022, is so important in putting forward voices that are regularly missing from fashionable art routes and blinkered contemporary art networks.

Although it can be said that the promotion of art practices attached to a specific identity position can be limiting, particularly if their meanings are only relatable within a particular context, I believe that good art can operate in multiple contexts and continue to convey meaning and insight in a variety of situations—transcending their labels whilst at the same time embracing them. FUTUROMA, the third Roma Exhibition, and the Venice Biennale, which I curated in 2019, aimed to present an example of this by staging works that carry universal meanings whilst also being grounded within a particular subjectivity. The choice of Mirga-Tas to represent Poland at the last Biennale in Venice is a further example of this universality and shows that art by Roma people is breaking through the barriers that have been in place for too long. I believe that such progressive moves can help toward addressing the continuing absence of works by Roma artists in museum collections and programming; a state that reflects a lack of commitment to addressing inequalities within the art establishment – and is of course a direct reflection of Roma inequality within wider society.

The consumption of art, its place in the construction of society’s culture, and the artist’s life itself are rare areas of research. However, artists, in addition to being producers, are also viewers, and as such, participants in the creation of social values and content. What art forms do you personally follow and what art content do you enjoy at the end of the day?

I visit exhibitions and museums regularly and when I travel, I try to see as much as I can within the visual arts. I have an eclectic taste when it comes to the kind of artworks that I find stimulating and all of these can be seen as influences in my work. Within the art world the graphic iconography of Pop Art, and the gestural mark-making of Abstract Expressionism, along with the serenity of Minimalism and the playfulness of Conceptual Art are top of my list. Optical illusions, puzzles, and word games also figure significantly.

I am also interested in vernacular forms of cultural production, as well as items resulting from domestic and communal art practices. More specifically objects that constitute the fabric of our everyday lives and that are often overlooked, a devaluation that renders these and cultural artifacts like them invisible. Modes of production employed to create these objects have been similarly devalued, especially in the art world. Part of the intention of my work is to invite us to consider again objects, processes, and themes that seem to inhabit previously neglected fields of production. My intention is for objects that may have been understood in a particular way to be re-encountered through their function as art objects.

I am also drawn to techniques used in ornamentation including gilding. Reverse glass painting is the process of painting onto the back of the glass, which is subsequently gilded with metal leaves. The application of the leaf produces a mirrored surface and the transformative potential of this process has been a recurring motif within my work. That this technique is associated with European folk art, particularly in Romania, adds to its allure for me given my fascination with practices that sit outside of the Western art canon. This transformative process, which is employed in the manufacture and ornamentation of everyday objects such as the mirror, highly embellished versions of which are common in Gypsy homes, makes it a useful vehicle for my studio practice, which seeks to navigate the area between Roma aesthetics and contemporary visual art language.

Ornamental objects which display multi-functionality also hold a special fascination for me. I have written extensively about such artifacts and their impact on my thinking and my art practice, and how they have formed the basis of my ongoing research into Roma aesthetics. Their influence can be seen in my studio practice which falls loosely into three major areas of production: Mirrors, Blankets, and Signs. Variations upon these motifs continue to motivate my artwork and even as I expand the subject matter and direction of my practice as an artist, I find myself returning to these dynamic vehicles of representation again and again.